CARTER FAMILY HISTORY

Our branch of the Carter family has been associated with the villages of Finchingfield and Wethersfield in Essex for many generations. We are also related to the Stock and French families of these villages.

To see the Carter Family Tree, click here.

The earliest photograph that we have of an ancestor is that of John James Carter who was born about 1858 in Finchingfield, Essex, England. He died in 1934. He married Mary (Polly) French, born about 1860 in Wethersfield, Essex, England. She died about 1940.

They lived in Rochester farmhouse, Main Road, Great Leighs.

Rochester Farm House and buildings, Main Street, Great Leighs, as it looks today.

In this 1915 picture John and Polly Carter are seated.

Standing behind them is their son Harry and wife, Ruth Carter.

Walter “Wally” Carter

Harry Arthur Carter, son of John James Carter and Mary (Polly) French was born in 1886 in Black Notley. He married Ruth, born in 1890 in Great Bardfield, the daughter of Walter Carter and Eliza Grubb.

Harry worked as a horse-breaker and farmer. He and Ruth spent some time in Great Totham where he had a job working with horses.  Harry and Ruth had 5 children. He died in August 1947 and Ruth in May 1950.

Harry and Ruth had 5 children. He died in August 1947 and Ruth in May 1950.  The Carter brothers Their four sons, Arthur John, Leslie Walter, Cyril and Bertie, were all born in Great Leighs, and a daughter, Mary Emily was born after the family had moved to Bradwell, where John James Carter had taken over the running of Goslings Farm. Harry and family lived in the cottages, and only moved into the main farmhouse after the death of his father.

The Carter brothers Their four sons, Arthur John, Leslie Walter, Cyril and Bertie, were all born in Great Leighs, and a daughter, Mary Emily was born after the family had moved to Bradwell, where John James Carter had taken over the running of Goslings Farm. Harry and family lived in the cottages, and only moved into the main farmhouse after the death of his father.

Goslings Farm, Bradwell

Goslings Farm, Bradwell

Leslie Carter’s wedding to Edna Jones

The reminiscences of Bradwell written down by Levi Hulme provide some insight into life there in those days: Levi arrived in Bradwell in 1917, working for 70 years there as a thatcher, hay trusser, woodman, haulage contractor and smallholder. Of Goslings Farm he states as follows: Goslings Farm When I came to Bradwell, it was farmed by a Mr Anderson, a Scotsman. He had a son Jim, who died in the war. After Mr Anderson it was farmed by Messrs Dyer and Franklin from Coggeshall, then taken over by Mr Rayner and sons from Tey. It was next taken by Mr John Carter and later by his son Harry who brought up his family there. Harry had four sons, two, Cyril and Bert, went in the forces leaving Arthur and Les to carry on with their father. Harry Carter was one of the hardest workers I have known. Walter Foster bought a piece of Goslings ground and had a bungalow built near Perry Green. Mr John Carter, who was a relative of Bill Batchford, let Bill take those little Charity Fields, which were farmed with Goslings, opposite Links Wood. Bill built up a pig and poultry farm there. After Mr Harry Carter died, the farm was split up, the cottages were sold, the farmhouse and 26 acres were sold and the rest of the farm split up between Mr Speakman and BradwellHall. There were two thatched barns on Goslings Farm which I thatched in my time. Two farm cottages at Goslings were sold when the farm was split up.

Farmwork & Ploughing in Essex, c. 1900

Farmwork & Ploughing in Essex, c. 1900

The Allotment Field Most of the village had a piece of ground on there. The rent was 3d a rod, collected by Mrs Norman and later by Harry. I helped Harry measure several of the pieces. When I married I started with 17 rod and ended up with 63 rod for a number of years. I kept pigs on there and used to grow a lot of stuff on there and sell some about the village. There is not much of it farmed today. The ground at the top was gardens for Fosters Cottages but in 1935 the Church Hall was built on two pieces. Then a piece was sold to Mr and Mrs Clark and the rest is now hard standing for cars. Source: Levi Hume ‘My 70 Years Living and Working in Bradwell’ Goslings Farm as it looks today:  Several members of the Carter family of Bradwell are buried in the grounds of Holy Trinity church.

Several members of the Carter family of Bradwell are buried in the grounds of Holy Trinity church.  Bradwell church stands quite a distance from the village and is mainly Norman with much evidence of roman bricks. Many churches in the vicinity of the Roman town of Colchester were constructed using bricks from the old roman buildings.

Bradwell church stands quite a distance from the village and is mainly Norman with much evidence of roman bricks. Many churches in the vicinity of the Roman town of Colchester were constructed using bricks from the old roman buildings.

REMINISCENCES OF MY CHILDHOOD

Bertie Carter

[son of Harry Arthur Carter and Ruth Carter, born on 17 September 1922 in Great Leighs.]

What’s the earliest memory you have? After we moved from Great Leighs to Bradwell and I was calling out for the lady who had brought me up a Mrs Lyons. I didn’t remember later on, but my parents had a helluva lot of trouble with me. According to what I’ve been told I spent 4 months with her and they made a great fuss of me. And then of course when we moved to Bradwell, I had to leave and go with the family. It was a terrible wrench for me and I think it has affected me the rest of my life. You don’t think about it when you are a child. I wish I knew more about my parents. They were very discreet. When I look back I think what a hard life they had. No modern conveniences. Slogging to make a living, poor old man had to go to get firewood for the copper to do washing on Monday. Where were you born? In Great Leighs into a family with 3 elder brothers, Arthur John, Lesley Walter and Cyril. My sister Mary Emily was younger than me and was born in Bradwell. Tell us some more about the story of Mrs Lyons. I never did find out how I came to be with her. I don’t know if she was a neighbour, I never wanted to hear about it. My brothers used to tease me about it. I wish there was somebody I could ask now and know all the answers, but that’s all gone now. I will never know what happened. I did hear my mother say that if she had 40 children she would never give another one away like that. Because I was a helluva trouble to them when they moved because I didn’t know my own mother. How old were you? I was only three when we moved to Bradwell, so I must have been about 2 I don’t know anything about it. All I know is that I was there long enough to forget my own mother. I remember them talking about it, and I remember my mother talking about it. Do you remember Mrs Lyons? I don’t. I think my mother went to see her later, after her husband died. What I’ve heard was that they doted on me, and used to take me up to this big house. I don’t know whether he was a gardener, he may well have been, from what I can gather. And I used to have to recite poetry in front of the lady of the house. I don’t remember anything about it but I’ve been told that’s what happened. So do you remember reciting poetry to your own family? Good God no. I don’t think I ever did.

Could Lyons Hall, Great Leighs be the house where Bertie recited poetry?

Could Lyons Hall, Great Leighs be the house where Bertie recited poetry?

What was your mother’s maiden name? Ruth Carter. She was a Carter, they were no relation, but she was a Carter. So what kind of a woman was she? Oh she was a marvellous mother, I couldn’t fault her. They had a very hard life, my Dad and my Mum. He was a tremendous worker. I have a letter from someone who said he was the hardest working man he’s ever known. What kind of work did he do? He was always a horseman, a farmer. He worked for other people at one time. They lived out at Great Totham at one point. He worked for a man out there who had horses. Cos he was a great one with horses. What did he do with horses? He used to break them in. When they were about two years old, he would break them in for work, so that they could be taken anywhere and put to work. They were Suffolk horses. They would have a pole in a meadow, and he would have a long rope, and he would run the horse round and round the pole and tire him out. Then he would start doing something with them, for example try to put a harness on them. Because they don’t like that. They would try to kick them off, and everything else. So he would put the collar over their heads, and the sandal on their backs. You’ve got to know what you’re doing when you break in a horse. You could no doubt have a lot of trouble. I think he was very adept at that. He used to get extra money for breaking in these horses from the farmer, I’ve heard my mother say. My grandfather had a farm at Great Leighs, Rochester’s farm which was on the main road. He lived there, he must have been a tenant farmer. What was your grandfather’s name? John James Carter. My grandmother’s name was Polly French. Did your father learn how to be a horse breaker from his father? I suppose so. I only remember my grandfather when he was just ‘the gov’nor’. I don’t remember my grandfather working with the horses.

Cyril Carter with one of the horses

Cyril Carter with one of the horses

Did your father teach you how to be a horsebreaker? My eldest brother was quite good with horses. He was fearless with horses, and fearless generally. He would come home at 12 o’clock at night and I have never known him to be afraid of anything. When he was doing the horsebreaking, did he have to do other things too? He would do a bit of horse breaking and then he would perhaps do a day’s work ploughing and whatever else was needed on the farm. My grandfather had an old hunter horse that he used to drive in his trap. And nobody could get in that cart and take the reins of that horse. Because the horse would tip the bloody cart over and everything else! The horse had been an old hunter and he picked it up cheap. It was quite a big horse. I remember it, Kit they called it. Uncle Fred would get on it and ride around and jump hedges and what not. Did your father teach you how to be a horsebreaker? My eldest brother was quite good with horses. He was fearless with horses, and fearless generally. He would come home at 12 o’clock at night and I have never known him to be afraid of anything. When he was doing the horsebreaking, did he have to do other things too? He would do a bit of horse breaking and then he would perhaps do a day’s work ploughing and whatever else was needed on the farm. My grandfather had an old hunter horse that he used to drive in his trap. And nobody could get in that cart and take the reins of that horse. Because the horse would tip the bloody cart over and everything else! The horse had been an old hunter and he picked it up cheap. It was quite a big horse. I remember it, Kit they called it. Uncle Fred would get on it and ride around and jump hedges and what not.  What did the cart look like? The cart was a two wheeler like a tug cart, what they used to run about it. My Dad took me over to see my grandparents in it. Dad took us in to the hospital when I was about 12 to have my tonsils out. My Mum asked if she could take me home. She looked out and saw the cart and said no way, he’ll have to go home in an ambulance, and I’ll get it a bit cheaper for you. It was the old Courtauld hospital. I had my tonsils out twice. I had them out when I was very young. They told my mother I would have to have my tonsils out. She said, he’s had them out. They said, they never took ‘em out properly. I remember going home in the ambulance to the farmhouse. My poor old grandmother was there and she said ‘you look like death, boy’. On my mother’s side my grandfather’s name was Walter and my grandmother’s name was Liza. Can you remember the house you grew up in? We lived in Goslings cottages for a few years until my grandfather died and we moved into the farmhouse after he died. Goslings was a horrible old place. Just a kitchen and a front room, two bedrooms upstairs and the attic at the top. We used to sleep in the attic, two of us. It used to be terribly bloody cold in the winter. My mother used to heat up a brick, wrap it and put it in the bed. We always had enough to eat, puddings and what not. They didn’t have a lot of money to throw around, but we always had enough to eat, probably not always the best of food but what could you say – they did their very best. Can’t add any more than that. He worked hard and so did she. They had a hard old life. Goslings was two attached cottages. The other cottage was rented out. Jennifer Ruggles’ Dad rented it for several years cos he worked on the farm down the road, Bradwell Hall. The nearest house was the gamekeeper’s house. Bradwell Hall farm was some distance away. So you didn’t have any neighbours? No we were very isolated. This was 1925 and they were just starting to build Silver End. We used to walk to school five days a week and to Sunday school. Did you ever ride a horse? Oh yes, from about the age of 10 onwards. When we were young they used to pick us up and put us on the horse. But it was later on that we used to climb on the horses ourselves and run them up and down. Arthur was the trouble-maker, he’d stir us up and what not, and mother couldn’t quieten us down and then she would wake father up, he’d be dozing and she’d say square these up Dad. And when he pulled his chair back we all scuttled, we knew there was trouble. Arthur got the brunt of it, he got the worst of the punishment. He used to get the hidings, while we used to creep out of the way quietly. I don’t think any of us did very well at school. We all went to Bradwell Church of England school. There were two school teachers, one taught the infants from ages 5 to 7 and the other teacher in the big room had all the rest, 40 to 50 children. She kept me in one dinner time. We used to take sandwiches at eat at school, and get a drink out of the brook which ran alongside the school. There were no taps in the school. They used to have to go down the village and get a bucket of water and stand it in the porch. On one occasion the teacher punished me and a school friend by keeping us in in a dinner time. “She said, you and Ivy Gally have been talking all morning, so she kept us both in, it didn’t bother me because I stayed to dinner anyway. Ivy had a younger brother who went home and soon afterwards there was a knock on the school door and in came Mrs Gally. She was only a small woman but did she fly off the handle, did she storm! Fancy keeping her in when its dinner time, you can’t do this! There was a helluva row, and Ivy went off with her.” I was probably about 8 or 9 at that time. I was 14 when I left school. My father had many a row with the old parson over that. Because he would keep me away from school if there was any work to do. I used to take the horses down to the blacksmith in the morning, course I’d be late for school then, then they would all jump up at the window and wave. He said, I keep my children, not you to the powers that be. Because the old parson was one of the school managers. We all left at 14. That’s how it was.

What did the cart look like? The cart was a two wheeler like a tug cart, what they used to run about it. My Dad took me over to see my grandparents in it. Dad took us in to the hospital when I was about 12 to have my tonsils out. My Mum asked if she could take me home. She looked out and saw the cart and said no way, he’ll have to go home in an ambulance, and I’ll get it a bit cheaper for you. It was the old Courtauld hospital. I had my tonsils out twice. I had them out when I was very young. They told my mother I would have to have my tonsils out. She said, he’s had them out. They said, they never took ‘em out properly. I remember going home in the ambulance to the farmhouse. My poor old grandmother was there and she said ‘you look like death, boy’. On my mother’s side my grandfather’s name was Walter and my grandmother’s name was Liza. Can you remember the house you grew up in? We lived in Goslings cottages for a few years until my grandfather died and we moved into the farmhouse after he died. Goslings was a horrible old place. Just a kitchen and a front room, two bedrooms upstairs and the attic at the top. We used to sleep in the attic, two of us. It used to be terribly bloody cold in the winter. My mother used to heat up a brick, wrap it and put it in the bed. We always had enough to eat, puddings and what not. They didn’t have a lot of money to throw around, but we always had enough to eat, probably not always the best of food but what could you say – they did their very best. Can’t add any more than that. He worked hard and so did she. They had a hard old life. Goslings was two attached cottages. The other cottage was rented out. Jennifer Ruggles’ Dad rented it for several years cos he worked on the farm down the road, Bradwell Hall. The nearest house was the gamekeeper’s house. Bradwell Hall farm was some distance away. So you didn’t have any neighbours? No we were very isolated. This was 1925 and they were just starting to build Silver End. We used to walk to school five days a week and to Sunday school. Did you ever ride a horse? Oh yes, from about the age of 10 onwards. When we were young they used to pick us up and put us on the horse. But it was later on that we used to climb on the horses ourselves and run them up and down. Arthur was the trouble-maker, he’d stir us up and what not, and mother couldn’t quieten us down and then she would wake father up, he’d be dozing and she’d say square these up Dad. And when he pulled his chair back we all scuttled, we knew there was trouble. Arthur got the brunt of it, he got the worst of the punishment. He used to get the hidings, while we used to creep out of the way quietly. I don’t think any of us did very well at school. We all went to Bradwell Church of England school. There were two school teachers, one taught the infants from ages 5 to 7 and the other teacher in the big room had all the rest, 40 to 50 children. She kept me in one dinner time. We used to take sandwiches at eat at school, and get a drink out of the brook which ran alongside the school. There were no taps in the school. They used to have to go down the village and get a bucket of water and stand it in the porch. On one occasion the teacher punished me and a school friend by keeping us in in a dinner time. “She said, you and Ivy Gally have been talking all morning, so she kept us both in, it didn’t bother me because I stayed to dinner anyway. Ivy had a younger brother who went home and soon afterwards there was a knock on the school door and in came Mrs Gally. She was only a small woman but did she fly off the handle, did she storm! Fancy keeping her in when its dinner time, you can’t do this! There was a helluva row, and Ivy went off with her.” I was probably about 8 or 9 at that time. I was 14 when I left school. My father had many a row with the old parson over that. Because he would keep me away from school if there was any work to do. I used to take the horses down to the blacksmith in the morning, course I’d be late for school then, then they would all jump up at the window and wave. He said, I keep my children, not you to the powers that be. Because the old parson was one of the school managers. We all left at 14. That’s how it was.

Bradwell village & school, c. 1900

I went with my Dad’s first cousin, Bill Batchford, he had a poultry farm. So I went and helped him for a year or two I used to bike there. He had a place where he would incubate his eggs, and when they hatched he had incubators with lamps on. They used to take them out to the fields after the wheat had been harvested. I worked with Bill for a couple of years then I went to Stisted where they were building army huts at the time, a builder from Hornchurch, A E Coran. I used to cycle. I helped do the concreting.

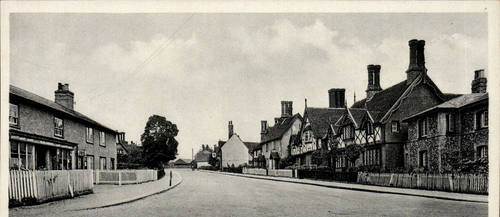

Stisted, c. 1930

Stisted, c. 1930

I worked with Jack Martin and his father-in-law who had come down from Tilbury, they had been bombed out. The father in law was a grumpy old man. He used to get on to his father-in-law, saying Bert and I are trying to help you, miserable old basket. I used to help Jack with the mixer and the barrows while the old man laid the floors down and then I used to help him tamp it down and level it. But he was a bitter old cuss. One night when we were knocking off, the police arrived on the scene. They were after Jack Martin. I reckon he’d had his call up papers and torn the bloody things up. He got hold of the policeman, saying ‘have you been round my house, frightening my missus?. And the copper said no . He said well bloody well don’t! He was an ex docker, I had never seen anyone get hold of a policeman like that. This was 1941, I was about 18 years old.

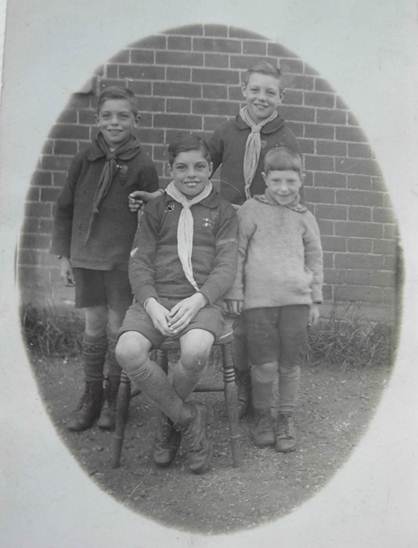

The elder Carter boys with cousin Chris Clowes from London

The elder Carter boys with cousin Chris Clowes from London

After we finished at Stisted, they began to build army huts at Leighs so I used to go there by bus. We used to take the bus from the Swan at Bradwell, go down to Braintree, and get another bus from there.

King George V – death announcement 21st January 1936 and funeral

King George V – death announcement 21st January 1936 and funeral

I remember that my uncle made a cabinet for our radio. He was a cabinet maker by trade. I remember when old King George V died. I remember hearing on the radio that the king’s life is drawing to an end. And I remember the farewell speech of the Duke of Windsor. I remember listening to that, and also hearing that a state of war had been declared. It was a Sunday morning at 11 o clock.

Philco Radio, 1941

Philco Radio, 1941

REMINISCENCES OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR

Bertie Carter

Where were you when the war broke out? At Goslings Farm. I was about 17 then. I was called up in 1942, when I was about 19. How did you feel when you were called up? I was quite happy about it. Cyril and myself were called up at the same time. We travelled up to London together from Witham and then we went our separate ways. He went down to Burgess Hill in Sussex. I went with another bloke from Coggeshall, and a man from Bradwell. Can you tell us about your war experiences? I had to go to Colchester for a medical after I was called up, and was passed fit. And I was asked what service do you want to join? I said the navy, but was told that the only vacancy was for stokers. I did not want to be a stoker, so the army it was, that’s how it came about. That was in February 1942. I had to do the basic training so they sent me down to Lark Hill, Salisbury Plain.

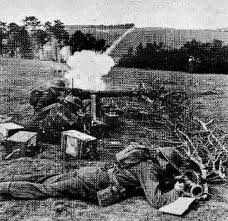

Training at Larkhill, 1942

Training at Larkhill, 1942

My brother and me were called up the same day but. I went down to Wiltshire. They met us off the train with lorries and took us to the camp. We had inoculations, it really knocked me out for a day or two. The training was pretty grim, very strict. It was a gruelling three months. I got on alright with the blokes in the hut. There were 20 or 30 in the billet. There was another chap from Coggeshall, but I didn’t know any of them before I arrived. Cyril and myself were both happy to be called up, we felt we should play our part like everyone else. I don’t know why they chose us rather than the older two. Arthur would have liked to have gone. He went into the Home Guard instead. Cyril went into the Service Corps and became a driver. We never met one another on leave. He went abroad long before I did. He went to north Africa and then on to Italy. He went all over north Africa but I don’t know the details. We never spoke much about the war together. He went from the bottom of Italy to the top, to the north. He used to talk about all the towns he’d been through. He saw a lot more than me, honestly. He had the time of his life, he had a very good time. After Salisbury I spent some time in Bicester, Oxfordshire. I have lost track of where we went and what we did after that. My memory has faded with time. I remember departing from Southampton. We were stuck in a field under canvas for a long while waiting for the order to cross the channel. It was a hot summer, we used to sit outside our tents playing cards. I remember Johnny Harris joining us for card games. I met up with him again later on, he became a friend.

|

|

We eventually embarked on a troop ship, and had to disembark into a little boat to take us to the beach. We had to go down a rope ladder to the boat. We bobbed around like a cork with our heavy back packs. Then we waded ashore. It was a very hot day. Then we formed up and marched to a field. There they said, Righto, dig in here, this is where we are staying the night. We had no tents or nothing we just went under bushes and wherever we could get shelter. Another chap from Yorkshire and myself dug in. Another chap was left on his own, and we invited him to join up with us in our dug-out. It started to rain and some of the lorries had pulled up in this field. So I said ‘lets get under the lorries to get out of the rain.’ The sergeant said, ‘no you bloody won’t. They might get bloody bombed! You stay where you are.’ The next day we moved off, closer to the fighting, and got stuck in another blooming field where a cow was tethered. The field was encircled with a dirt track and our shelter became the ditch. I had to go on guard with another man. We were supposed to patrol the field each going opposite ways and to meet up in the middle of the dirt track I kept patrolling my side but I never saw the man I was supposed to reconnoitre with. I thought to myself, ‘I don’t know where the hell he’s got to’. I didn’t know him. Suddenly the officer came round. I had to halt him and ask to be recognised. He said ‘Where’s the other man, I’ve been right round and not seen him’. I said, ‘I don’t know, I’ve been going round and not met up with him. I don’t know what’s happened to him’. He went off and reported it to the sergeant. This bloke had got in with the other blokes in the ditch. I never saw him again. I expect he was court martialled. It was a serious matter, abandoning your post. They whisked him away. This would have been 1944. We were up near Caen, Normandy. The hedgerows were white with dust up there. Then we went up through Falaises, passing dead horses and animals lying about. Then suddenly we were whipped into lorries and taken to Belgium. When we got there it was a sunny afternoon I remember it well, I think we were the first troops the villagers of this particular place had seen. We were heading towards a chateau with a big lawn, and a tree lined drive leading up to it. A tremendous place. The village was Klein Vorst, the nearest town wasTessenderlo [a municipality located in the Belgian province of Limburg]. Officer Slater said to me, ‘Carter, you’ve drawn the short straw’. I said, ‘That’s nothing unusual’. He said ‘You’ll be first on guard. Don’t let anybody in’. There was a big gateway. ‘Nobody must come in. Keep everybody out’. He then told the sergeant ‘Relieve Carter as soon as possible. As soon as the lads have had their dinner’. Kids kept coming up to me, and a large crowd of villagers were looking on. I was eventually taken off duty to have my dinner and it was decided to place two sentries on duty. The sergeant said, ‘We’ve got to be on the alert tonight, because I think the Jerries will try to recapture this place’. They had left in a hurry leaving food, rifles, bedding behind. They had made a quick exit. It was afraid that Germans would parachute in, so the guard was doubled. We ended up there a long while, however, because winter had drawn in and the advance had got stuck. A big mistake had been made at Arnhem and a lot of men had been lost. Parachuters had gone in but the Germans were waiting for them. So everything got held up and we stayed at this place for weeks on end. It was unusual because we had been constantly on the move. We took the chateau over and it was alright in there. Lovely place. We used to go out in a gang of 3 or 4. We used to go down to the town where the café was, and we could get a Belgian beer. Sunday night was when dances were held. We went into a café one time with some lovely girls. Freddie Ward, Johnnie Harris and myself we were having a right old time. We went a few times dancing at Klein Vorst. We used to get sort of pissed up and what not. That’s what we went for, to drink. We had a whale of a time when we used to go these places. On one occasion I went to one of these cafes with Johnny Harris. Of course John had the impression they were all brothels. We went into this cafe, not far from where we were camped. and we bought some beer. We sat down at the bar. Two beautiful girls came in. I think there was the two of us. There was a flight of steps that went up near us. The two lovely girls went up the steps. Johnny says, come on, Bert, let’s go up the stairs. These two girls stood at the top, looking down you see. The Barman said “No You Bloody Well don’t! I can speak English, I know what’s going on”. He could speak English because he’d been a barman in London. The girls were his daughters. He told us he’d been a barman in London. And that was that. Johnny had the impression all these places were brothels and he was all for it. Apparently he had a nice girl in England. I never did meet her. She was a school teacher and she used to write every day. She used to send him parcels and stuff, but I don’t think he used to write back to her. Freddy Moore, his best mate, said ‘That’s bloody good, he never even writes home. Johnny, you’ll have to write to her, otherwise we won’t get any more parcels!’ When we used to get the post, the corporal coming one day said ‘never mind lads, they’re all for Harris. And they were. 7 letters for him that day. They would build up, you see, because the post would get delayed. He said ‘here you are, read that one’. I said ‘I don’t want to read your bloody mail.’ He did not even read them all. But If there was any other girls about, he’d be there. Johnny Harris was from Rhyll North Wales. Freddy Moore was from Sheffield. He was an extrovert. He got caught out one day. There was another chap with us, a nice quiet lad, named Peter Self. He was a nice lad, he never said a lot. He used to have these terrible smelly feet when he took off his socks or whatever. These others, bloody blokes, Moore and Harris in particular, used to yell at him “Your bloody feet Selfy.” I piped up for him. I said he washes his feet just as much as we do. He washes his socks just as much as what we do. Sometimes we had no facilities, he couldn’t help it. Anyhow, one day there was a bit of shinddy between Moore and Selfy. He was getting onto to Selfy about something. Selfy the quiet chap didn’t fancy his chances at fisticuffs or anything like that. But that day he got his bristles up, and he put the bloody wind up Moore – he thought Selfy was going to lay into him. He never had no bloody cheek from Moore after that, he put him in his place. Selfy was quite pleased with himself when he told me all this what happened. He said I don’t think Moore has got a lot of guts in him.’ I said, ‘No I don’t think he has’. He was an extrovert and a big man in his way. He thought he was cock of the walk. But that pulled him down a bit when Selfy stood up to him.  Bertie Carter [right] with Mr King from Billericay, in 1944, probably taken at Klein Vorst Where did you go when you finally left Klein Vorst? We went to Holland but we didn’t stay there long. We moved further up. At that time, they hadn’t crossed the Rhine. They were getting ready to cross the Rhine into Germany, when I was up in Holland. I don’t remember where we were, we were in some bloody village. We had passed through Eindhoven. Around that time they sent me down to the first aid post to the medical officer to have a medical. They were weeding out the younger blokes, to go back to England, with a plan to send them to Burma, that was the idea to send them to the Far East. Because the war was nearly over in Europe, but was still going on there. The medical officer I was sent to was Canadian. At the time I had this big boil on my arm. I couldn’tget any treatment for it, The cook used to try and put a hot poultice on it, to burst it. He said because of the boil I’ll give you the choice. Because he either had to pass me as fit or not. So he gave me the alternative. he could either leave me there or I could go back to England. So I said well I’ll take a chance and go back. So we went back from there, back to Bruges Belgium. It was a sort of shunting off place there. We think we were in a dusty old place for a couple of days. There were no beds there, we had to sleep on the floor. Then we went to Ostend to get the boat across the channel and we docked at Tilbury. We all came from different units and everybody was talking about where they lived and where we were going. Some who lived near a garrison said we were going to that place. Some said we were going to Colchester. Then we got on a train and it transpired that we were headed to Yorkshire. Noone had surmised that! We got up there early in the morning, and marched from the station to the barracks. And went into the billet and they said we’ll sort you out in the morning. We didn’t get there till 4 am and they had us up again at 6. Then we were sorted into different platoons. I was put into B company with a crowd of blokes I didn’t know. Lucky I got in there, I was under a sergeant Nichols, bloody nice fellow. He was one of the best, sergeant Nichols was. Then there was sergeant Kent and sergeant Moore. There were three platoons in the company. And the little old sergeant major, little old Jordan, like a little bantam cock he was. He got the military medal. Sergeant Nichols apparently didn’t like him, he said it should have been Sergeant Kent who had it. He said Kent was leading that patrol, when they got caught up in this ambush and got themselves out of it that won them the medal. It should have been Sergeant Kent. Somehow or other the sergeant major ended up with it. Nichols was a real tough. We used to be the last bloody platoon on the square for the morning parade. All the platoons used to line up for inspection. This was in Pickering in Yorkshire. We were on parade one morning, and there was three of us always last out of the hut. There was Westwood, a Londoner and Duffy a Scotsman. They were both big chaps. Anyhow we were on parade this morning. We used to borrow each other’s things. We were always the last three out of the hut. The sergeant would be shouting let’s be having yer, the bloody parade’ll be over! Westwood always went to the front row on the left hand side. Duffy and me used to try to juggle about in the rear rank. Sargeant Nichols use would be shouting let’s have some front rank soldiers. Then we’d march to the square for inspection. This particular day, big inspection, one of the top blokes. Came round, and round. Suddenly, a tap on my shoulder. I thought, bloody Christ. I’m in for it now. Then He said ‘a good soldier never looks behind’. He said, ‘clean the back of your boots next time. And after we got off parade, Sargeant Nichols said, Christ he said, “I’ve never known him to do that before. You’ve got a bloody lucky charm Carter.’ Any other time he would have said, ‘take that man’s name sergeant.’ And you know, I would have been on a charge. But he must have been in a good mood. I would have got a few days CV or a few days detention. At about 10 o’clock at night we would go up in the Yorkshire moors on a night exercises, with blackened faces and all that. We did all sorts. Then we’d go on the firing range. What we used to do, three of us at that time. We were firing 303s, rifles. There used to be three of us at a time. The pits would be at the other end, where they used to mark up. We used to have a NCO, sergeant major or whatever. The NCOs would stand by the side of us while we shoot, sort of coaching you, seeing where the shots went. One morning, one of those miserable April days, damp and cold. We finished our shooting and were waiting to get home. We sat around a big cardboard box of sandwiches which hadn’t been eaten. The Sergeant Major was up on the range, coaching someone. Suddenly he hsouted down ‘One of you chaps bring me a sandwich’. Nobody moved. So he called again. ‘One of you chapsbring me a sandwich. ‘Nobody stirred. We all looked at each other. Nobody was going to be chicken and go. The next time he called, he probably found out Ball was there, because he was a big chap. So he called out ‘Ball!’ Ball was furious. So Ball bawled out, ‘Is that the only bloody name you know sergeant major!’ So the sergeant major called out ‘Right, Fall in two men. Take him to the Guard Room.’ So when we got back to camp, he was stuck in the guard room. He got so many days. We helped him out with cigarettes and that while he was in detention. That’s how it was. He got caught out because he had the shortest name. He had a short fuse anyway, old Ball did. Sometimes he’d take pride in his uniform, sometimes he’d be slovenly. He didn’t care. I think at one time he had a stripe, but he lost it because he couldn’t discipline himself. Tell us about your Belgian girlfriend. Clotilda – she was a lovely girl she was. Her surname was Goos. Her mother was a big woman her father was a small man. She had 2 sisters. She was in the middle. Nice people they were. That was in the village of Klein Vorst, near Tessenderlo, Diest. I don’t know what happened to her. What happened to your other friends? Johnny Harris and Moore came back to England got transferred to the E Yorks, and they went to a place called Helmsey near Malta. I had no means of transport to get down to see them. I didn’t see them again. Where did you go after Yorkshire? I had a month’s agricultural leave. To help with the harvest because it was summertime. In the meanwhile my unit had moved down to Warwickshire. I was due back on a Thursday, but my sister was getting married on the Saturday. I wanted to hang on for the wedding. I wrote to them and asked for an extension. What they done, they sent me a telegram ‘report back at once’. So I thought, well, the wedding’s Saturday, so I stayed over. I went back on Monday. In the meanwhile the regimental police called at my house, to see where I was. A civilian copper from Witham also came for me. My mother said ‘he’s gone back this morning.’ The copper said that’s good job, save me a lot of trouble.’ These bloody redcaps, though, they were a bit sarky. She could soon get her bristles up and she gave as good as she got. She said ‘you’ll have to find him wherever he is’. So I got to Liverpool Street, and from there I had to get to Paddington. I went to the canteen there and had my dinner. The platform was full of people, you know. But I saw bloody red cap, a sergeant, I dodged behind some old woman. He half turned and twigged me, he said ‘hey wait a minute.’ He said ‘you got a pass?’ I said ‘yeah’. He said ‘where is it?’ I pulled it out. He said ‘you’re four days adrift.’ I said ‘I know I am, I’m going back.’ He said ‘I think you better come with me.’ So we went to the station. There was another redcap there. They started to discuss what to put on the form; one said he’d put ‘when charged’ the other one said no, you have to put ‘when apprehended’. They were having a bit of difficulty to spell ‘apprehended’. But In the end, that is what they put down. Not charged, apprehended. They said you got to go down to Scotland Yard. They had a little van outside with a WAF driver. I jumped in the van and so did one of them. So they took me down there. I had to see the bloke in charge of the cells. He took my wallet and braces, and boot laces. So I didn’t kill myself. They said you’ll get it all back when you get out. They took me down to the cell. They were just going to have their tea, so I went with the bloke in my cell to this great hall. I said I didn’t want any tea. He said ‘you get it, I’ll eat it. Or if you’re in here long enough you’ll bloody want it.’ They used to take the food back to the cells. So I took the grub with me and what not. This was about 8 or half past 9 in the evening. They said ring the bell if you want to go to the toilet. In the early hours of the morning or sometime they opened the bloody cell door and shoved a bloody guardsman with his arm in his sling. We had to scrub the cell. They used to chuck a blanket into you at night before lights out. Then one of the warders came over to me and said you can’t have 3 to a cell, so they put me in a different cell, and I had to scrub that bloody cell out too. So then the warder come to me, and said as you are on your own, you better come out and sweep the hallway. So I scrubbed the floor. I talked to another chap, he said how long were you absent when they caught you? I said 4 days. He said that’s nothing I’ve been absent a year. So he was expecting a real old do, being absent a year. IN the morning they shoved another bloody man in my cell. He was cursing his bad luck. He said he had been absent a year when he got caught. He said he was working all that time, and he used to come by the jail every day. On that particular day it was raining so he decided to take to the bus. He was wearing his army coat, and was waiting in the queue, but he didn’t have his hat on, so the redcap stopped him for being improperly dressed, and nabbed him. So of course he was roped in with me. He was telling me all his tale. He said that bloody rain. I got this coat on, but no hat. When the redcap stopped him he had no paperwork. My escort had come for me by this time and I had to go out. I went to the reception where they gave me my wallet and things back. They told me not to talk to the escort. The escort was an Irish chap, a sergeant, a bloody nice bloke, he said I wanted to come up last night he said; but the old man wouldn’t wear it. I live in London, and if I had come up last night, I’d have got you out, and we could have stayed at my place, we could have gone out and hada few beers. They know who they are coming to get. So we marched down to the station, walked through the town. There was some women there, they were waiting for a bus, they called out’ bloody great bullies, poor little bugger’. The sergeant, being Irish, had a quick retort, he called back, ‘don’t worry Madam he won’t take any harm with us’. The same red cap that picked up me up was at the station. The sergeant asked me if I wanted tea or cakes, I said no. The red cap said the train will be full, hang on a minute and I’ll get a sticker and put it on the car ‘reserved for military prisoners’. So we had an empty carriage. One red cap slumped on one side for a sleep and one on the other. But as the train pulled off the sergeant called out to a woman and a child, you can come in here with us, we’re harmless. During the journey, everyone was fast asleep. I wanted to go to the toilet, so I had to wake up the sergeant. He said ‘that’s alright Bert, you go, you’re not going to jump off the train are you?’ I said ‘hardly likely’. When we got off the train, he had to take me to the guard room to go in front of the commanding officer. He said, ‘if you had returned, I’d have got you home the next day. But I’m only going to give you 7 days CB [confined to barracks]. So he was very lenient to me. He could have made it a lot worse for me. He was a good sort.

Bertie Carter [right] with Mr King from Billericay, in 1944, probably taken at Klein Vorst Where did you go when you finally left Klein Vorst? We went to Holland but we didn’t stay there long. We moved further up. At that time, they hadn’t crossed the Rhine. They were getting ready to cross the Rhine into Germany, when I was up in Holland. I don’t remember where we were, we were in some bloody village. We had passed through Eindhoven. Around that time they sent me down to the first aid post to the medical officer to have a medical. They were weeding out the younger blokes, to go back to England, with a plan to send them to Burma, that was the idea to send them to the Far East. Because the war was nearly over in Europe, but was still going on there. The medical officer I was sent to was Canadian. At the time I had this big boil on my arm. I couldn’tget any treatment for it, The cook used to try and put a hot poultice on it, to burst it. He said because of the boil I’ll give you the choice. Because he either had to pass me as fit or not. So he gave me the alternative. he could either leave me there or I could go back to England. So I said well I’ll take a chance and go back. So we went back from there, back to Bruges Belgium. It was a sort of shunting off place there. We think we were in a dusty old place for a couple of days. There were no beds there, we had to sleep on the floor. Then we went to Ostend to get the boat across the channel and we docked at Tilbury. We all came from different units and everybody was talking about where they lived and where we were going. Some who lived near a garrison said we were going to that place. Some said we were going to Colchester. Then we got on a train and it transpired that we were headed to Yorkshire. Noone had surmised that! We got up there early in the morning, and marched from the station to the barracks. And went into the billet and they said we’ll sort you out in the morning. We didn’t get there till 4 am and they had us up again at 6. Then we were sorted into different platoons. I was put into B company with a crowd of blokes I didn’t know. Lucky I got in there, I was under a sergeant Nichols, bloody nice fellow. He was one of the best, sergeant Nichols was. Then there was sergeant Kent and sergeant Moore. There were three platoons in the company. And the little old sergeant major, little old Jordan, like a little bantam cock he was. He got the military medal. Sergeant Nichols apparently didn’t like him, he said it should have been Sergeant Kent who had it. He said Kent was leading that patrol, when they got caught up in this ambush and got themselves out of it that won them the medal. It should have been Sergeant Kent. Somehow or other the sergeant major ended up with it. Nichols was a real tough. We used to be the last bloody platoon on the square for the morning parade. All the platoons used to line up for inspection. This was in Pickering in Yorkshire. We were on parade one morning, and there was three of us always last out of the hut. There was Westwood, a Londoner and Duffy a Scotsman. They were both big chaps. Anyhow we were on parade this morning. We used to borrow each other’s things. We were always the last three out of the hut. The sergeant would be shouting let’s be having yer, the bloody parade’ll be over! Westwood always went to the front row on the left hand side. Duffy and me used to try to juggle about in the rear rank. Sargeant Nichols use would be shouting let’s have some front rank soldiers. Then we’d march to the square for inspection. This particular day, big inspection, one of the top blokes. Came round, and round. Suddenly, a tap on my shoulder. I thought, bloody Christ. I’m in for it now. Then He said ‘a good soldier never looks behind’. He said, ‘clean the back of your boots next time. And after we got off parade, Sargeant Nichols said, Christ he said, “I’ve never known him to do that before. You’ve got a bloody lucky charm Carter.’ Any other time he would have said, ‘take that man’s name sergeant.’ And you know, I would have been on a charge. But he must have been in a good mood. I would have got a few days CV or a few days detention. At about 10 o’clock at night we would go up in the Yorkshire moors on a night exercises, with blackened faces and all that. We did all sorts. Then we’d go on the firing range. What we used to do, three of us at that time. We were firing 303s, rifles. There used to be three of us at a time. The pits would be at the other end, where they used to mark up. We used to have a NCO, sergeant major or whatever. The NCOs would stand by the side of us while we shoot, sort of coaching you, seeing where the shots went. One morning, one of those miserable April days, damp and cold. We finished our shooting and were waiting to get home. We sat around a big cardboard box of sandwiches which hadn’t been eaten. The Sergeant Major was up on the range, coaching someone. Suddenly he hsouted down ‘One of you chaps bring me a sandwich’. Nobody moved. So he called again. ‘One of you chapsbring me a sandwich. ‘Nobody stirred. We all looked at each other. Nobody was going to be chicken and go. The next time he called, he probably found out Ball was there, because he was a big chap. So he called out ‘Ball!’ Ball was furious. So Ball bawled out, ‘Is that the only bloody name you know sergeant major!’ So the sergeant major called out ‘Right, Fall in two men. Take him to the Guard Room.’ So when we got back to camp, he was stuck in the guard room. He got so many days. We helped him out with cigarettes and that while he was in detention. That’s how it was. He got caught out because he had the shortest name. He had a short fuse anyway, old Ball did. Sometimes he’d take pride in his uniform, sometimes he’d be slovenly. He didn’t care. I think at one time he had a stripe, but he lost it because he couldn’t discipline himself. Tell us about your Belgian girlfriend. Clotilda – she was a lovely girl she was. Her surname was Goos. Her mother was a big woman her father was a small man. She had 2 sisters. She was in the middle. Nice people they were. That was in the village of Klein Vorst, near Tessenderlo, Diest. I don’t know what happened to her. What happened to your other friends? Johnny Harris and Moore came back to England got transferred to the E Yorks, and they went to a place called Helmsey near Malta. I had no means of transport to get down to see them. I didn’t see them again. Where did you go after Yorkshire? I had a month’s agricultural leave. To help with the harvest because it was summertime. In the meanwhile my unit had moved down to Warwickshire. I was due back on a Thursday, but my sister was getting married on the Saturday. I wanted to hang on for the wedding. I wrote to them and asked for an extension. What they done, they sent me a telegram ‘report back at once’. So I thought, well, the wedding’s Saturday, so I stayed over. I went back on Monday. In the meanwhile the regimental police called at my house, to see where I was. A civilian copper from Witham also came for me. My mother said ‘he’s gone back this morning.’ The copper said that’s good job, save me a lot of trouble.’ These bloody redcaps, though, they were a bit sarky. She could soon get her bristles up and she gave as good as she got. She said ‘you’ll have to find him wherever he is’. So I got to Liverpool Street, and from there I had to get to Paddington. I went to the canteen there and had my dinner. The platform was full of people, you know. But I saw bloody red cap, a sergeant, I dodged behind some old woman. He half turned and twigged me, he said ‘hey wait a minute.’ He said ‘you got a pass?’ I said ‘yeah’. He said ‘where is it?’ I pulled it out. He said ‘you’re four days adrift.’ I said ‘I know I am, I’m going back.’ He said ‘I think you better come with me.’ So we went to the station. There was another redcap there. They started to discuss what to put on the form; one said he’d put ‘when charged’ the other one said no, you have to put ‘when apprehended’. They were having a bit of difficulty to spell ‘apprehended’. But In the end, that is what they put down. Not charged, apprehended. They said you got to go down to Scotland Yard. They had a little van outside with a WAF driver. I jumped in the van and so did one of them. So they took me down there. I had to see the bloke in charge of the cells. He took my wallet and braces, and boot laces. So I didn’t kill myself. They said you’ll get it all back when you get out. They took me down to the cell. They were just going to have their tea, so I went with the bloke in my cell to this great hall. I said I didn’t want any tea. He said ‘you get it, I’ll eat it. Or if you’re in here long enough you’ll bloody want it.’ They used to take the food back to the cells. So I took the grub with me and what not. This was about 8 or half past 9 in the evening. They said ring the bell if you want to go to the toilet. In the early hours of the morning or sometime they opened the bloody cell door and shoved a bloody guardsman with his arm in his sling. We had to scrub the cell. They used to chuck a blanket into you at night before lights out. Then one of the warders came over to me and said you can’t have 3 to a cell, so they put me in a different cell, and I had to scrub that bloody cell out too. So then the warder come to me, and said as you are on your own, you better come out and sweep the hallway. So I scrubbed the floor. I talked to another chap, he said how long were you absent when they caught you? I said 4 days. He said that’s nothing I’ve been absent a year. So he was expecting a real old do, being absent a year. IN the morning they shoved another bloody man in my cell. He was cursing his bad luck. He said he had been absent a year when he got caught. He said he was working all that time, and he used to come by the jail every day. On that particular day it was raining so he decided to take to the bus. He was wearing his army coat, and was waiting in the queue, but he didn’t have his hat on, so the redcap stopped him for being improperly dressed, and nabbed him. So of course he was roped in with me. He was telling me all his tale. He said that bloody rain. I got this coat on, but no hat. When the redcap stopped him he had no paperwork. My escort had come for me by this time and I had to go out. I went to the reception where they gave me my wallet and things back. They told me not to talk to the escort. The escort was an Irish chap, a sergeant, a bloody nice bloke, he said I wanted to come up last night he said; but the old man wouldn’t wear it. I live in London, and if I had come up last night, I’d have got you out, and we could have stayed at my place, we could have gone out and hada few beers. They know who they are coming to get. So we marched down to the station, walked through the town. There was some women there, they were waiting for a bus, they called out’ bloody great bullies, poor little bugger’. The sergeant, being Irish, had a quick retort, he called back, ‘don’t worry Madam he won’t take any harm with us’. The same red cap that picked up me up was at the station. The sergeant asked me if I wanted tea or cakes, I said no. The red cap said the train will be full, hang on a minute and I’ll get a sticker and put it on the car ‘reserved for military prisoners’. So we had an empty carriage. One red cap slumped on one side for a sleep and one on the other. But as the train pulled off the sergeant called out to a woman and a child, you can come in here with us, we’re harmless. During the journey, everyone was fast asleep. I wanted to go to the toilet, so I had to wake up the sergeant. He said ‘that’s alright Bert, you go, you’re not going to jump off the train are you?’ I said ‘hardly likely’. When we got off the train, he had to take me to the guard room to go in front of the commanding officer. He said, ‘if you had returned, I’d have got you home the next day. But I’m only going to give you 7 days CB [confined to barracks]. So he was very lenient to me. He could have made it a lot worse for me. He was a good sort.

Mary Carter’s wedding to Tom Evans, with Harry and Ruth Carter also pictured.

Mary Carter’s wedding to Tom Evans, with Harry and Ruth Carter also pictured.

This was the event that led to Bertie being locked up for the night in Scotland Yard!

What happened next? After that I had to hang about for a posting, because my lot had gone off. So they sent me off to Staffordshire to a Prisoner of War camp. I had to go there and be one of the guards. I was posted on my own with all my kit, and the station master said it’s uphill about 6 miles from here. You can’t get up there with all that kit. So he rang up the camp for me. They sent a truck to pick me up. I hadn’t been there a day or so when they said you’ve got to go to the ‘low down’ camp. It was great down there because there was only a sergeant in charge. It was a sort of overflow prison for the main camp. The sergeant in charge was a Scotsman. He was alright, we hardly saw him. We used to post a guard on the main gate in daytime and a guard at night. There were one or two corporals and they didn’t bother much either; I think everyone was looking forward to getting out at that time. They used to let all the prisoners out on a Sunday afternoon and let them wander about on their own. I said to Corporal May, isn’t anyone going to go with them? He said ‘well do you want to go!’ I said ‘no,’ he said ‘there’s only bloody fields, there’s nowhere for them to run to.’ They put one of the senior prisoners in charge, a former U-boat commander. He used to take charge of the prisoners during their walks. These were German prisoners. If they hung their washing on the line at night, our blokes used to pinch anything good on the line. I didn’t do that, I had my own kit. These were blokes who used to flog their own kit for a pint of beer and then pinch the gear of the Germans. I remember the young fellow who was the hair dresser. He was from Hamburg. He used to cut the hair of the guards who were on that camp. This was in 1945 and I came out of the army in 1946.

German POWs in England

German POWs in England

Tell us about any other memories of the war? I went to a couple of camps. I got moved from Staffordshire into Warwickshire close to Leamington Spa. This was a camp with Ialian prisoners of war. One of those Italian blokes, he was worse to the prisoners, than any of us. He had some position of authority, he was a nasty bloke. If ever he got back to Italy and he had come across any of them, they would have killed them. What were the circumstances of your leaving the army? A mate of mine said ‘youre on company orders, Bert, 9 o clock.’ I said ‘Good God.’ This meant I had to go and see the commanding officer. He told me ‘your papers have come through.’ 25 company was due to go out having done their time, but he said ‘you can be released due to being an agricultural worker. You can go out with 25 group, go to Hereford, pick up your suit.’ My documents were got ready and I went off the next day. They kitted you out with a civilian suit, trilby hat, everything. Then I had to go back to camp, and get my box and travelled home the next day. I got caught in a tube rush. A lady on the escalator said to me ‘let me carry that box boy,’ because I had a load of kit and my overcoat. I think this must have been in February 1946, because I went into the army in February 1942. So I did 4 years. Cyril was still in Italy or Austria then. What jobs did you do after you left the army? For a time I worked with my father, because that was the agreement I came out with. I then went to work for Mr Spekeman for a while. And he told me I needed to work full time for tax purposes. Cyril also used to work for him. They had a rent-free detached house calledHighview, Bradwell that belonged to Mr Spekeman, and I lodged there. After the war while I was still single I made two trips to Ireland with my brother in law Tom Evans. Tommy’s parents lived in Mullingar [south of Ireland, 50 miles from Dublin]. Tommy’s mother looked after the [Church of England] church. Their house probably belonged to the church. She kept the church clean and looked after it. Tommy’s father used to have to clear weeds from the church yard path. He was a lot older than her and did not want to be disturbed. We used to spend a lot of time in the Pubs . In those days there were no regular hours. They used to check if coast was clear – no garda about – and out you would come. On a Sunday ifthey saw a garda coming down the road they would hustle everyone upstairs out of the way. It took a day’s drive to get to Skibereen [where Tom’s uncle still lived. On the way, there used to be several rest stops, and we would always dash into a pub.

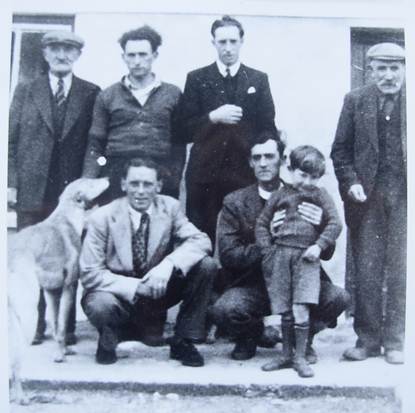

In the picture are back row: Tom’s Dad, Tom’s cousin, Bertie,and Tom’s uncle.

In the picture are back row: Tom’s Dad, Tom’s cousin, Bertie,and Tom’s uncle.

Front row’ Tom, Tom’s cousin [elder brother to the cousin in the back row] holding his son.

The picture was taken in Skibereen, where the Evans family hail from.

I first worked for the Eastern electricity board for five years. Digging pole holes, and trenches and laying cables. Then I went on the hedge cutting gang. There were only three of us, we had a van and used to cut down the hedges that were growing near the lines. Nice little number that was! I used to work with Fred Woods. One day he was digging a hole in the road, and a car came by and decapitated him. Poor old boy. In 1961 I went to Courtaulds to work in the textile factory at Bocking. I didn’t stay in the factory long because I asked for a transfer. I couldn’t stand working in a front of a machine all day – fabric was being dried in a hot stenter – and each roll had to be put on and taken off. There was a bloke at one end and me at the other. I got transferred to the warehouse. I went to the loading bay. Everything that came in we took off, and reloaded the lorries. The lorries used to come in from Spondon in Derbyshire. Courtaulds had taken it over from British Ceylonese. After I had been doing this for a time, the bloke in charge said I’ve got to send somebody to work with Tom King. He was an ex sergeant-major who had done 30 years in the armhy. He was very regimental. He said there’s no good asking anyone else because they will just put on their jackets and go home. So I went up, and he said are you the bloke from downstairs. And I seemed to be getting on ok, so the bloke on the loading bay said I don’t want to lose you, but he keeps asking for you, so I went up there. I stayed a long while up there. He was very good to me. I said to him one day, I will never know this job like you do Tom. He said you will one day, you’re young. One day you will be the next floor controller. Idid get offered the job, I carried on for a while. But then I said to George Penny, the manager, I don’t want the responsibility. He said ‘no, no, we’re not going to accept that, go home and talk it over with your wife’. I went back and did the job, I did the same work, but Dave Parry, a Welshman in charge of the invoicing, took charge. They got in trouble with the retailing once, and the bloke who was in charge in London, came to see me. His orders hadn’t been done, so he stirred it all up. Hewent to see Mr Tom King, who said in no uncertain terms, see Mr Penny. Then he came up and there was quite an upheaval. They all gathered round my desk and discussed what to do. The manager said to me ‘we’ve been caught with our trousers down Bert, we’ve been caught out. So we’ve got to do what we can to rectify the situation. So he wanted me to stay on that night. But Tom King said to me ‘don’t stop – they’re in the shit leave them to it’. He was my supervisor so I wanted to row in with King, so I left. Eventually, they had to give me permission to stay whenever I wanted to and work as long as liked. King never stopped. At 5 pm he went home. He lived on his own on the caravan site. He had been married and divorced. But he had a lady friend in the office. She was a jilted spinster, who had taken a long while to get over it. She had had a nervous breakdown. And they did eventually get married. He said ‘she will inherit my pension which will be good for her.’ He also bought her car. Her name was Joyce Duncan, of Stisted. Les Butcher was another friend of mine. He worked in the warehouse on a different floor. It was a four storey building. We used to meet up in the morning and have a chat. He was a widower and lived at home with his mother. His wife had gassed herself. They had just had a baby, who was only a few weeks old when she died. Les brought the boy up. I introduced him to Barbara Adams whose husband had died. He eventually married Barbara.

PART TWO

In 1957 Bertie married Nives Seri. Nives was born on 18 July 1935 at 17 Vicolo San Fortunato, Trieste, Italy. The wedding took place at StistedChurch and the picture of Nives and Bert is taken at Highview, Bradwell.  Also in this picture are Bertie’s sister Mary and her son Eammon, Bertie’s brother Cyril with his wife Quintillia and their sons Gordon and Douglas, Bertie’s brothers Arthur and Leslie with Leslie’s wife Edna and their daughters Sandra and Linda.

Also in this picture are Bertie’s sister Mary and her son Eammon, Bertie’s brother Cyril with his wife Quintillia and their sons Gordon and Douglas, Bertie’s brothers Arthur and Leslie with Leslie’s wife Edna and their daughters Sandra and Linda.

This 1963 photograph shows Bertie and brother Cyril with wives Nives and Quintillia [Lia] and Bertie’s children Paul [aka Tom] and Marina. The house in the background belonged to Cyril and Lia. Bertie and family lived next door in the village of Cressing.

WW2 troopship

WW2 troopship

Recent Comments